Contemplations

|

|

Contemplation archives |

by Rev. Paul Corman

Most of us like to travel. I certainly do. It is important to have a goal or purpose to the travel but it isn’t just the travel itself that matters. There is preparation before a trip: reading about places to visit, maybe learning a little of a new language, deciding on a route, arranging transportation, packing and finally starting off. Planning means being prepared to improvise! Emotions can arise even before the journey begins: joy, anticipation of getting away from daily burdens, perhaps anxiousness about unknown adventures. Travel is an integral part of human life. Life is often spoken of as a journey between birth and death. And what if the journey continues after death or begins before birth? That would be a journey in the realm of spirit as exciting as any to the most exotic of earthly places, a journey needing as much or more aforethought and preparation: reading about the realm of spirit, learning its language, loosening matter’s overbearing hold on us by unpacking the things stored in our soul suitcase, sorting them out, deciding what to leave behind and what to take, re-packing our soul with thoughts and images that can serve in finding our way in the Spirit. But, you know, we do go to the land of spirit quite often. Thinking, fantasising, remembering, praying, are excursions into this vast land. Each night, though unconscious of it, we go there in sleep. We are not such inexperienced travellers in Spirit; we need not be tourists there. We live in that world as well as in the world of matter. We are citizens of both. We may not recognise or appreciate its beauty and all it has to offer, but instead of being a tourist we can become adventurers, explorers. The sacraments of The Christian Community can sustain and assist us along both our Earth and Spirit paths. The Gospels are a guide for such travel. In them the Christ speaks of the way. He prepares the disciples and advises them before sending them out on the Christ-Journey. Each of us can become such Christ-Travellers. We have the same travel guide as the disciples did. We have the sacraments to encourage and enliven our journey and we have the Christian festivals through the year to remind us of the relevance of the journey and its goal.

Especially the festivals of this season: Advent, Christmas and Epiphany do that. “Advent” means “come or go toward”. But who is travelling, where to or from? The Christ Child, to us; we, to Him or both? “Advent” shares a language root with “adventure”. Advent is a time to become as awake as possible that our life is a great adventure, one which has meaning to be sought and found, one in which there is a meeting up with our destiny, with the Christ in us and in others. He is coming toward us; we are going toward Him. Advent is a caring for growth and for that which will be born. Experience the growth of a creative process by painting or sketching and working on it daily during the month, or writing a poem or story bit by bit. Study a skill or craft or subject you have always wanted to learn and watch yourself grow day by day. Learn a bit of Gospel, a verse or other writing of value by heart slowly but surely over the days of Advent. These are a few of the ways to celebrate Advent as an adult and not just vicariously for the children. The Spanish word for Christmas, “Navidad”, gives another clue to the great journey. It shares a root with our words, “navigate” and “navy”. Ours is a journey onto the ocean of the forces that permeate all life and since the Mystery of Golgotha are the dwelling place of Christ. It is from out of these Christ permeated life forces that we are born anew each morning. They become more powerful and more effective when we recognise their existence and contemplate their workings in earthly matter. Epiphany is perhaps the epitome of the human journey on Earth, following an ideal like a.star shining with grace above us, guiding and orienting us all along our way. The Wise Magi did that and found the highest human ideal. Our journey, whatever seeming detours it takes, through adventures, pains and joys, is to that same goal. So a proper greeting for this season might be, have a good journey, enjoy the trip and God speed.

Most of us like to travel. I certainly do. It is important to have a goal or purpose to the travel but it isn’t just the travel itself that matters. There is preparation before a trip: reading about places to visit, maybe learning a little of a new language, deciding on a route, arranging transportation, packing and finally starting off. Planning means being prepared to improvise! Emotions can arise even before the journey begins: joy, anticipation of getting away from daily burdens, perhaps anxiousness about unknown adventures. Travel is an integral part of human life. Life is often spoken of as a journey between birth and death. And what if the journey continues after death or begins before birth? That would be a journey in the realm of spirit as exciting as any to the most exotic of earthly places, a journey needing as much or more aforethought and preparation: reading about the realm of spirit, learning its language, loosening matter’s overbearing hold on us by unpacking the things stored in our soul suitcase, sorting them out, deciding what to leave behind and what to take, re-packing our soul with thoughts and images that can serve in finding our way in the Spirit. But, you know, we do go to the land of spirit quite often. Thinking, fantasising, remembering, praying, are excursions into this vast land. Each night, though unconscious of it, we go there in sleep. We are not such inexperienced travellers in Spirit; we need not be tourists there. We live in that world as well as in the world of matter. We are citizens of both. We may not recognise or appreciate its beauty and all it has to offer, but instead of being a tourist we can become adventurers, explorers. The sacraments of The Christian Community can sustain and assist us along both our Earth and Spirit paths. The Gospels are a guide for such travel. In them the Christ speaks of the way. He prepares the disciples and advises them before sending them out on the Christ-Journey. Each of us can become such Christ-Travellers. We have the same travel guide as the disciples did. We have the sacraments to encourage and enliven our journey and we have the Christian festivals through the year to remind us of the relevance of the journey and its goal.

Especially the festivals of this season: Advent, Christmas and Epiphany do that. “Advent” means “come or go toward”. But who is travelling, where to or from? The Christ Child, to us; we, to Him or both? “Advent” shares a language root with “adventure”. Advent is a time to become as awake as possible that our life is a great adventure, one which has meaning to be sought and found, one in which there is a meeting up with our destiny, with the Christ in us and in others. He is coming toward us; we are going toward Him. Advent is a caring for growth and for that which will be born. Experience the growth of a creative process by painting or sketching and working on it daily during the month, or writing a poem or story bit by bit. Study a skill or craft or subject you have always wanted to learn and watch yourself grow day by day. Learn a bit of Gospel, a verse or other writing of value by heart slowly but surely over the days of Advent. These are a few of the ways to celebrate Advent as an adult and not just vicariously for the children. The Spanish word for Christmas, “Navidad”, gives another clue to the great journey. It shares a root with our words, “navigate” and “navy”. Ours is a journey onto the ocean of the forces that permeate all life and since the Mystery of Golgotha are the dwelling place of Christ. It is from out of these Christ permeated life forces that we are born anew each morning. They become more powerful and more effective when we recognise their existence and contemplate their workings in earthly matter. Epiphany is perhaps the epitome of the human journey on Earth, following an ideal like a.star shining with grace above us, guiding and orienting us all along our way. The Wise Magi did that and found the highest human ideal. Our journey, whatever seeming detours it takes, through adventures, pains and joys, is to that same goal. So a proper greeting for this season might be, have a good journey, enjoy the trip and God speed.

A Community of the Living and the Dead

by Rev. Michaël Merle

The night of the thirty-first of October is Halloween (All Hallows' Eve) and marks the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day (All Saints' Day). This ancient feast day in the Christian calendar sets November aside as the month of the year when those who have crossed the threshold into the worlds of Spirit are very consciously remembered.

In the tradition of the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Church, in particular, the second of November is All Souls' Day. Here the soul journey of those who have died and have not yet entered the peace and rest of Heaven are remembered. This purgative time was described by Rudolf Steiner as the experience of kamaloca: "Man passes through the kamaloca period which lasts roughly a third of the length of his earthly life - in reverse sequence...He really does go through his whole life backwards, right to the moment of birth. This is what is behind the beautiful words of Christ, when He was speaking of man's entry into the spiritual world or the Kingdom of Heaven: 'Except ye...become as little children, ye shall not enter into the Kingdom of Heaven!' In other words, man lives backwards as far as his first moments and being absolved of everything, he can enter the Kingdom of Heaven, and be in the spiritual world from then onwards." (The Being of Man and his Future Evolution: Lecture 6: Illness and Karma - Berlin, 26 January 1909, GA107) Kamaloca is an experience of living through the pain we have caused others - both consciously and unconsciously. This experience is not a punishment but rather a necessary purgation - a purifying so that we can experience an absolution and our being is thus truly purified in love.

November carries the signature that we form one community of the living and the dead. Those who have crossed the threshold of life on earth to life in the Spirit remain part of our community of faith. The active remembering of those who have died is a true service of love for the wholeness of the communion of saints, of which we are all a part. The tradition of such is one of this community's many virtues: a group gathers on the last Saturday of every month in remembrance of those who have died.

This sense of the oneness of our humanity sets the scene for our stepping into the beginning of our Festive Year with the celebration of Advent. In conclusion of the month of November with the Remembering of the Dead and on the last Sunday of the Church year Rev. Reingard Knausenberger will be giving an address following the tea after the Act of Consecration of Man, entitled: 'Is Reincarnation a Matter-of-course?', which will focus on the realities we face beyond the threshold.

The night of the thirty-first of October is Halloween (All Hallows' Eve) and marks the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day (All Saints' Day). This ancient feast day in the Christian calendar sets November aside as the month of the year when those who have crossed the threshold into the worlds of Spirit are very consciously remembered.

In the tradition of the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Church, in particular, the second of November is All Souls' Day. Here the soul journey of those who have died and have not yet entered the peace and rest of Heaven are remembered. This purgative time was described by Rudolf Steiner as the experience of kamaloca: "Man passes through the kamaloca period which lasts roughly a third of the length of his earthly life - in reverse sequence...He really does go through his whole life backwards, right to the moment of birth. This is what is behind the beautiful words of Christ, when He was speaking of man's entry into the spiritual world or the Kingdom of Heaven: 'Except ye...become as little children, ye shall not enter into the Kingdom of Heaven!' In other words, man lives backwards as far as his first moments and being absolved of everything, he can enter the Kingdom of Heaven, and be in the spiritual world from then onwards." (The Being of Man and his Future Evolution: Lecture 6: Illness and Karma - Berlin, 26 January 1909, GA107) Kamaloca is an experience of living through the pain we have caused others - both consciously and unconsciously. This experience is not a punishment but rather a necessary purgation - a purifying so that we can experience an absolution and our being is thus truly purified in love.

November carries the signature that we form one community of the living and the dead. Those who have crossed the threshold of life on earth to life in the Spirit remain part of our community of faith. The active remembering of those who have died is a true service of love for the wholeness of the communion of saints, of which we are all a part. The tradition of such is one of this community's many virtues: a group gathers on the last Saturday of every month in remembrance of those who have died.

This sense of the oneness of our humanity sets the scene for our stepping into the beginning of our Festive Year with the celebration of Advent. In conclusion of the month of November with the Remembering of the Dead and on the last Sunday of the Church year Rev. Reingard Knausenberger will be giving an address following the tea after the Act of Consecration of Man, entitled: 'Is Reincarnation a Matter-of-course?', which will focus on the realities we face beyond the threshold.

"Wakefulness"

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

One day the Buddha was sitting in concentration and was serene, when a Brahmin priest walked past and says: ‘I’ve never seen anything like you. Are you a god?’ ‘No,’ said the Buddha.’ Are you an angel or a spirit?’ ‘No’ said the Buddha. ‘Well, what are you?’ And the Buddha said: ‘I’m awake!’

The writer who brings this story of the Buddha, Karen Armstrong, goes on to say that “…religion is not an anaesthetic”, but is something which encourages a wakeful standing-in-the-midst of life’s turbulence.” There are images which symbolize this in all religions…” for Christianity she cites the picture of Jesus on the cross, “in charge of his death.” (taken from: “Conversations on Religion” p183ff)

The theme of wakefulness played a significant part at the founding events of The Christian Community. It was at the end of the two weeks in September 1922, all the ordinations had taken place and three of the now-priests had celebrated the Act of Consecration of Man. The final step remained, that of ceremonially handing over the biretta, one on behalf of all the group. That in itself carried then and carries now a strong gesture of wakefulness within the priestly vestments: I walk to the altar, I put the biretta to one side when the priest-in-me celebrates. I wear it when I speak my own words, etc.

On that September morning the closing words then followed and the vote of thanks, by Fr. Rittelmeyer, for all that Rudolf Steiner had contributed, not least of all with his closing remarks regarding the weeks and months which lay ahead for these 45 pioneers of religious renewal. He had stressed the need for wakefulness, in all that they would undertake, even that they should be on their guard for opponents and attacks from other religious streams. “Watch and wake” comes to mind from the Garden of Gethsemane (Mt. 26) …”that your truth can be effective” (Rudolf Steiner).

It sounds like an example of Michaelic consciousness, an example of one of the attributes of Michael, to be awake, alert. And in the context of The Christian Community, now a movement fast approaching 100 years in age, it is tempting to add a further note: we can continue to be wakeful, generally, and equally with regard to challenges from different sides. Let’s also extend our wakefulness for others who are similarly sensing the import for religious renewal, in other places, with other backgrounds, individuals and groups. The Christian Community is not alone…no longer alone, in this striving.

One day the Buddha was sitting in concentration and was serene, when a Brahmin priest walked past and says: ‘I’ve never seen anything like you. Are you a god?’ ‘No,’ said the Buddha.’ Are you an angel or a spirit?’ ‘No’ said the Buddha. ‘Well, what are you?’ And the Buddha said: ‘I’m awake!’

The writer who brings this story of the Buddha, Karen Armstrong, goes on to say that “…religion is not an anaesthetic”, but is something which encourages a wakeful standing-in-the-midst of life’s turbulence.” There are images which symbolize this in all religions…” for Christianity she cites the picture of Jesus on the cross, “in charge of his death.” (taken from: “Conversations on Religion” p183ff)

The theme of wakefulness played a significant part at the founding events of The Christian Community. It was at the end of the two weeks in September 1922, all the ordinations had taken place and three of the now-priests had celebrated the Act of Consecration of Man. The final step remained, that of ceremonially handing over the biretta, one on behalf of all the group. That in itself carried then and carries now a strong gesture of wakefulness within the priestly vestments: I walk to the altar, I put the biretta to one side when the priest-in-me celebrates. I wear it when I speak my own words, etc.

On that September morning the closing words then followed and the vote of thanks, by Fr. Rittelmeyer, for all that Rudolf Steiner had contributed, not least of all with his closing remarks regarding the weeks and months which lay ahead for these 45 pioneers of religious renewal. He had stressed the need for wakefulness, in all that they would undertake, even that they should be on their guard for opponents and attacks from other religious streams. “Watch and wake” comes to mind from the Garden of Gethsemane (Mt. 26) …”that your truth can be effective” (Rudolf Steiner).

It sounds like an example of Michaelic consciousness, an example of one of the attributes of Michael, to be awake, alert. And in the context of The Christian Community, now a movement fast approaching 100 years in age, it is tempting to add a further note: we can continue to be wakeful, generally, and equally with regard to challenges from different sides. Let’s also extend our wakefulness for others who are similarly sensing the import for religious renewal, in other places, with other backgrounds, individuals and groups. The Christian Community is not alone…no longer alone, in this striving.

“Lazarus, the ‘one whom God aids’”

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

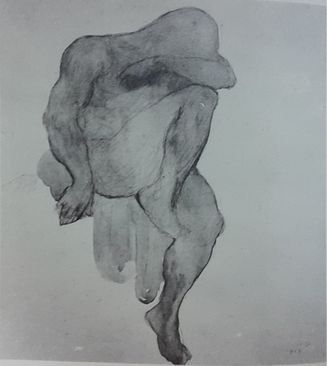

How well chosen a name can be. In his nakedness (see picture) his godly nature can emerge.

Unroll like a fern in the Spring.

Church of Lazarus. A place where one is “aided and abetted”, by God. Our innermost core.

Which calls forth and is called forth.

Kahlil Gibran, whose portrayal of Lazarus this is, wrote a one-act play at the end of his relatively short life, suggesting what Lazarus’ experience beyond the threshold might have been, and his challenges on returning. He wrote the play in its present form in the 1920s, long before the prevalence of ‘near death’ and ‘out of the body’ experiences, which tackle some of the same issues that concerned Gibran: "Who understands that which I have encountered beyond the threshold?" (Gibran's Lazarus refers to it as his 'beloved'.) "How, if at all, can I accommodate that experience with the comparatively humdrum daily life recommencing as if nothing had happened?"

The sense of being alone, even of loneliness, is very strong. It is an objective fact of being on earth, that within the communities of family, friends, work, society, nationality, we are also unavoidably alone in our separate bodies. Anything which faces us existentially will remind us of the fact. For the Lazarus portrayed by Gibran, and for those who have had such profound spiritual experiences, this earth-bound ‘being alone’ has been put into another perspective, into a larger picture of spiritual connectedness. But how to integrate that into the apparent confines of existence on this side of the threshold? And is the number of people with such experiences going to continue increasing, thus increasing the need for an understanding of their accounts and their questions?

If we call our meeting place the “Church of Lazarus”……what are we implying, what are we offering, to friends, members, newcomers? Surely a place where, “aided by God”, the threshold between worlds and the bridging thereof, is of central importance. The resurrected spirit of Lazarus was the greatest deed of Christ Jesus in the lead-up to the events of Easter itself. He didn’t return to life simply to continue where he had left off before his illness took hold. In that there would have been little point and much frustration, as Kahlil Gibran describes. Lazarus returns to begin a new chapter of life, out of a completely new insight into the greater human potential.

How well chosen a name can be. In his nakedness (see picture) his godly nature can emerge.

Unroll like a fern in the Spring.

Church of Lazarus. A place where one is “aided and abetted”, by God. Our innermost core.

Which calls forth and is called forth.

Kahlil Gibran, whose portrayal of Lazarus this is, wrote a one-act play at the end of his relatively short life, suggesting what Lazarus’ experience beyond the threshold might have been, and his challenges on returning. He wrote the play in its present form in the 1920s, long before the prevalence of ‘near death’ and ‘out of the body’ experiences, which tackle some of the same issues that concerned Gibran: "Who understands that which I have encountered beyond the threshold?" (Gibran's Lazarus refers to it as his 'beloved'.) "How, if at all, can I accommodate that experience with the comparatively humdrum daily life recommencing as if nothing had happened?"

The sense of being alone, even of loneliness, is very strong. It is an objective fact of being on earth, that within the communities of family, friends, work, society, nationality, we are also unavoidably alone in our separate bodies. Anything which faces us existentially will remind us of the fact. For the Lazarus portrayed by Gibran, and for those who have had such profound spiritual experiences, this earth-bound ‘being alone’ has been put into another perspective, into a larger picture of spiritual connectedness. But how to integrate that into the apparent confines of existence on this side of the threshold? And is the number of people with such experiences going to continue increasing, thus increasing the need for an understanding of their accounts and their questions?

If we call our meeting place the “Church of Lazarus”……what are we implying, what are we offering, to friends, members, newcomers? Surely a place where, “aided by God”, the threshold between worlds and the bridging thereof, is of central importance. The resurrected spirit of Lazarus was the greatest deed of Christ Jesus in the lead-up to the events of Easter itself. He didn’t return to life simply to continue where he had left off before his illness took hold. In that there would have been little point and much frustration, as Kahlil Gibran describes. Lazarus returns to begin a new chapter of life, out of a completely new insight into the greater human potential.

"Good News, Bad News. Positive News."

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

“Oh, there is so much bad news in the world everyday! Wherever you look – where will it all end?”

The cry is familiar, the examples hardly need repeating, let alone that we dwell on them here. They are as familiar to us as the above response. What a relief when we hear of something good, that even finds its way into the media pages – be it a distant royal wedding, a good-mood “Walk the Talk” event, a medal at the Olympics. Some good news is simply good. A lot of good news is particularly so because it stands in direct or indirect relationship to something else, a prior event, which weighed more heavily on the people concerned. A highlight in the year of many Irish villages is the annual amateur dramatics festival. Some of these have been running for sixty years now, initiated as an antidote to the post-war gloom of loss and unemployment, still lifting the communities today from their cares and concerns. The excellent work of countless charities is another example, as they respond to need and suffering, be it locally or internationally.

Bad news. Good news. And positive news? A subtle difference seems to be implied. An expression which has been receiving attention and support in recent years is “Constructive Journalism”, which provides us with a clue. One definition from that quarter is:

“Oh, there is so much bad news in the world everyday! Wherever you look – where will it all end?”

The cry is familiar, the examples hardly need repeating, let alone that we dwell on them here. They are as familiar to us as the above response. What a relief when we hear of something good, that even finds its way into the media pages – be it a distant royal wedding, a good-mood “Walk the Talk” event, a medal at the Olympics. Some good news is simply good. A lot of good news is particularly so because it stands in direct or indirect relationship to something else, a prior event, which weighed more heavily on the people concerned. A highlight in the year of many Irish villages is the annual amateur dramatics festival. Some of these have been running for sixty years now, initiated as an antidote to the post-war gloom of loss and unemployment, still lifting the communities today from their cares and concerns. The excellent work of countless charities is another example, as they respond to need and suffering, be it locally or internationally.

Bad news. Good news. And positive news? A subtle difference seems to be implied. An expression which has been receiving attention and support in recent years is “Constructive Journalism”, which provides us with a clue. One definition from that quarter is:

Another way of describing ‘positive news’ would then be to say that it is not simply replacing the bad with the good (“feel-good fluff”), but that it is interested in the relationship between the two, trying to identify examples of transformation. Surely this is much more deeply satisfying for the human soul, which can only stomach so much bad – or good – news, that another level is accessed, which embraces both realities. Is it going too far to say that this approach is ‘holistic’, trying to take in the greater picture, overcoming the duality of bad versus good?

|

We can apply this approach to the recent Gospel Reading, Mark 8, where Christ foretells for the first time what lies ahead – His suffering, death and overcoming of death. These events are intimately connected and challenge one to see them, not as bad followed by good, but as being intricately woven with each other, interdependent. Together they build the necessary turning point in human development.

To that comes something further; the pronouncement of Christ’s is initiated by someone’s recognition: Peter’s indication that he, and the Disciples, are almost ready to grasp this greater reality. That will become the paving stones to take them through the ‘bad and good’ of the Golgotha events. Peter illustrates here how central the inner involvement is, which we can bring towards an understanding of so-called outer events, which in turn impacts greatly on their subsequent unfolding. The spiritual component is therewith also visible, in a truly constructive relationship with the so-called bad and good in our lives.

An interesting footnote: The “constructive journalism” world declared five years ago that 24th June be their day in the year on which such projects from around the world confer and concertedly further this approach. Coincidence that it is also the declared festival day of John the Baptist?

To that comes something further; the pronouncement of Christ’s is initiated by someone’s recognition: Peter’s indication that he, and the Disciples, are almost ready to grasp this greater reality. That will become the paving stones to take them through the ‘bad and good’ of the Golgotha events. Peter illustrates here how central the inner involvement is, which we can bring towards an understanding of so-called outer events, which in turn impacts greatly on their subsequent unfolding. The spiritual component is therewith also visible, in a truly constructive relationship with the so-called bad and good in our lives.

An interesting footnote: The “constructive journalism” world declared five years ago that 24th June be their day in the year on which such projects from around the world confer and concertedly further this approach. Coincidence that it is also the declared festival day of John the Baptist?

"Rituals and Sacraments"

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

A further contribution to this subject – which provided the theme for the two recent Community Gatherings is reprinted below. It comes from Christward Kröner, who some will remember from his time as a newly ordained priest here in Johannesburg, at the beginning of the nineties. He wrote it as part of a booklet for the recent Whitsun Conference in Holland and it seems apposite here. (See elsewhere in the Newsletter for further related contributions). I wonder who the 'eminent contemporary' is, whom he quotes....

A further contribution to this subject – which provided the theme for the two recent Community Gatherings is reprinted below. It comes from Christward Kröner, who some will remember from his time as a newly ordained priest here in Johannesburg, at the beginning of the nineties. He wrote it as part of a booklet for the recent Whitsun Conference in Holland and it seems apposite here. (See elsewhere in the Newsletter for further related contributions). I wonder who the 'eminent contemporary' is, whom he quotes....

Although The Christian Community is approaching its 100th birthday, it is still at its very beginning. Today the religious life of many people no longer includes fixed forms and social commitment, so our movement might seem as a living anachronism. However, The Christian Community does not “oppose” the times, nor is it “behind the times”. On the contrary, its current validity and future potential must be discovered – and developed – again and a gain. The Christian Community recognises the religious maturity of every person, respects the freedom of belief and each individual’s innermost convictions, and trusts that divine revelation and divine presence can take place in every human soul. In this regard, it is very different from many things that have historically developed as “church”. |

“The Bridge Builders”

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

Amongst the pioneers of a new movement or enterprise, one often finds those who have a particular concern for its relationship to existing institutions and schools of thought. This has, in part, to do with an interest in that which is also alive in the surroundings and in an openness for dialogue, building bridges across which a stimulating exchange and growing point can develop for all concerned. Equally it can be someone in an existing institution who reaches out for dialogue with that which is new.

An example of such a bridge builder was Arthur Shepherd, better known as A.P. Shepherd, and perhaps best known in Christian Community circles for his book “The Scientist of the Invisible”, a biography of Rudolf Steiner, written in 1954. He was ordained into the Anglican Church in 1911, where he remained active all his working life. In about 1940 he became interested in the work of Rudolf Steiner in relation to Christianity. From that point onward all that had already lived in him found its re-affirmation and its expression in much of his writing and in the talks and sermons he gave. He contributed regularly to the newspaper, articles on the Christian path, as well as for BBC broadcasts. One such article is included here, taken from his book, published posthumously, entitled “The Battle for the Spirit”.

Amongst the pioneers of a new movement or enterprise, one often finds those who have a particular concern for its relationship to existing institutions and schools of thought. This has, in part, to do with an interest in that which is also alive in the surroundings and in an openness for dialogue, building bridges across which a stimulating exchange and growing point can develop for all concerned. Equally it can be someone in an existing institution who reaches out for dialogue with that which is new.

An example of such a bridge builder was Arthur Shepherd, better known as A.P. Shepherd, and perhaps best known in Christian Community circles for his book “The Scientist of the Invisible”, a biography of Rudolf Steiner, written in 1954. He was ordained into the Anglican Church in 1911, where he remained active all his working life. In about 1940 he became interested in the work of Rudolf Steiner in relation to Christianity. From that point onward all that had already lived in him found its re-affirmation and its expression in much of his writing and in the talks and sermons he gave. He contributed regularly to the newspaper, articles on the Christian path, as well as for BBC broadcasts. One such article is included here, taken from his book, published posthumously, entitled “The Battle for the Spirit”.

Ascension – Whitsun – Trinity

The three last festivals of the Church’s year follow one another so swiftly in the space of two and a half weeks that one may wonder why they are so crowded and fail to see their intimate relationship as the highest peak of Christian revelation. The life and death of Christ were over, and in the victory of His resurrection He had banished for ever the fear that man is only a creature of space, whom death annihilates; and had revealed to him the indestructibility of that inner soul-experience of which he is conscious, yet finds so fugitive and uncertain. Yet still the scene of Christ’s action was directed earthwards, to the human soul-life of His apostles, to whom He showed Himself alive and whom He taught truths of the spirit that only now their hearts could comprehend.

Suddenly the scene expands from earth to the pure spirit realm of Man’s true being. “In their sight He ascended up into heaven.” The description of that last physical manifestation is applied with too literal concepts, as of a material body that can only be in one place at a time, as though Christ, having ascended, has left the earth for His seat at the right hand of God. But Saint Paul in his Epistle to the Ephesians (Ch. 4:7) gives the true picture. “For that He ascended, what does it imply but that He descended, even to the lower parts of the earth, that He might fill all things.” In the spirit world, movement is not a change of location, but the expansion of consciousness and activity. The divine-human being of Christ, which had been manifest in physical form, is now exalted to fill the whole realm of being from the physical to the divine.

And from this realm of Man’s true being He poured down its spiritual faculties and potentialities. “He ascended up on high and gave gifts unto men.” Not only, for a while, the strange unearthly gifts of diverse tongues of power over sickness and the evil forces of nature, but above all like a sea engulfing them the downpouring of that divine love which is the foundation of spirit being, “the love of God shed abroad in our hearts through the Holy Ghost.” Not only deliverance from the taint of our earthly past, and from the fear of the certain end of death, but now a foretaste of our true being and existence.

“Because ye are sons of God, God hath sent forth the spirit of His son into your hearts.”

Finally, with that foretaste of heaven in the gifts of the spirit, our vision is lifted up beyond ourselves and our earthly existence to the mystery of the Godhead itself. Trinity Sunday is not the feast of an incomprehensible dogma, but a vision of the source and fount of our Redemption which is expressed to us in the Mystery of the Trinity in Unity; or as Christ Himself spoke it: “I in them and Thou in me, that they may be perfected into the one.” It is the crowning vision of the Christian revelation.

God Almighty and with Him

Cherubim and Seraphim,

Filling all eternity.

Adonai Elohim!

“Between Light and Dark”

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

It is a theme which came up strongly in the course of the Holy Week evening contemplations. It emerges there almost inevitably, archetypally. It is, however around us throughout our life, in effect on a daily basis: Light, Dark and the Space Between.

During the first days of Holy Week, Palm Sunday to Tuesday particularly, the polarities of light and dark are very pronounced. On the one hand there resounds the excitement, celebration, euphoria around the arrival of “the Awaited One”. On the other hand the forces gain momentum which deny Jesus Christ being that awaited Saviour. Light and dark qualities are centre stage. Helpfully though, this example from Holy Week doesn’t quite fit into the common interpretation of light equalling good, dark equalling bad. The mood is rather one of earthly soul extremes; overly excarnated and irrational, overly incarnated, stuck. (Is it the difference, metaphorically, between blinded and blind?)

How is that with a sentence such as “Christ’s light in our daylight”, which we know from the Act of Consecration of Man throughout the year? This becomes very tangible in the mid-week events of Holy Week, providing a picture which is relevant for daily life altogether. Into the polarities of those first days Christ introduces something completely different, from within Himself. Looking back and looking forward, He introduces soul qualities into the evolving events, inner qualities which are transformative for the future.

It is a theme which came up strongly in the course of the Holy Week evening contemplations. It emerges there almost inevitably, archetypally. It is, however around us throughout our life, in effect on a daily basis: Light, Dark and the Space Between.

During the first days of Holy Week, Palm Sunday to Tuesday particularly, the polarities of light and dark are very pronounced. On the one hand there resounds the excitement, celebration, euphoria around the arrival of “the Awaited One”. On the other hand the forces gain momentum which deny Jesus Christ being that awaited Saviour. Light and dark qualities are centre stage. Helpfully though, this example from Holy Week doesn’t quite fit into the common interpretation of light equalling good, dark equalling bad. The mood is rather one of earthly soul extremes; overly excarnated and irrational, overly incarnated, stuck. (Is it the difference, metaphorically, between blinded and blind?)

How is that with a sentence such as “Christ’s light in our daylight”, which we know from the Act of Consecration of Man throughout the year? This becomes very tangible in the mid-week events of Holy Week, providing a picture which is relevant for daily life altogether. Into the polarities of those first days Christ introduces something completely different, from within Himself. Looking back and looking forward, He introduces soul qualities into the evolving events, inner qualities which are transformative for the future.

|

Three examples which we looked at are the following:

Firstly, in the daily journey to and from Bethany, or in the life-long dedication of a person such as Mother Teresa, flows more than a dedication to duty – it is an outpouring of love, for humanity. The second example came as the tension increased and the net closed around Christ and the Disciples; the sense for the truth of Christ’s calling became paramount - for Him and for his Disciples. Doubt or uncertainty had no place. Thirdly, forgiveness. Already this can be felt on the Wednesday as a soul quality directed towards those whose deeds were still to follow. Love, Truth, Forgiveness, and more besides these three, create the anchor between the light and dark of life-events. They are dependent on the meeting between life’s polarities, without which they cannot grow and transform. |

Easter Contemplation

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

An April Newsletter spans the greatest divide of recorded history. Chapters and epochs of the earth have come, gone and been replaced by new ones, all with a sense of being part of, and under the guidance of a divine plan. Recorded history is marked by the divine guidance now coming via seers, sages, prophets – incarnate channels for that guidance and, most importantly, the responsibility for that plan and guidance being increasingly shared with human beings.

An unprecedented depth of entrusting humanity with the ability to be co-carriers of that divine plan, marks the turning point in recorded history. Until then inspiration and intuition had flowed more or less freely through the spiritual leaders. Now, that flow would enter into earth substance itself – a unique gift, a world moment, that meant an unparalleled “before and after”, the greatest divide of recorded history. The Mystery of Golgotha.

March giving way to April is a reminder of this, a living reminder within the soul, as we try and span that divide: looking in one direction at the decline of living processes, in the other direction at new potential and with humanity increasingly with the reins in their own, individual and collective hands. The Saturday of Holy Week, between Christ-Jesus’ dying and becoming, is that microcosmic moment, the platform from which we feel that divide…and try to bridge it within ourselves. To do that implies, however humbly or inadequately, embracing the two sides; of decline, death and of the possibility to overcome, transform to new life. The gift of Christ.

An unprecedented depth of entrusting humanity with the ability to be co-carriers of that divine plan, marks the turning point in recorded history. Until then inspiration and intuition had flowed more or less freely through the spiritual leaders. Now, that flow would enter into earth substance itself – a unique gift, a world moment, that meant an unparalleled “before and after”, the greatest divide of recorded history. The Mystery of Golgotha.

March giving way to April is a reminder of this, a living reminder within the soul, as we try and span that divide: looking in one direction at the decline of living processes, in the other direction at new potential and with humanity increasingly with the reins in their own, individual and collective hands. The Saturday of Holy Week, between Christ-Jesus’ dying and becoming, is that microcosmic moment, the platform from which we feel that divide…and try to bridge it within ourselves. To do that implies, however humbly or inadequately, embracing the two sides; of decline, death and of the possibility to overcome, transform to new life. The gift of Christ.

In so many ways mankind still lives in a dualistic mind-set, a mindset of polarities and opposites. For example, the binary world which has globalised so much of our life, communication, etc. has this as its inherent challenge, to get beyond the ‘either/or’ and to embrace the seemingly disconnected poles. How to do this, and the real value therein, is described by the poet and writer David Whyte, from his particular vantage point:

“We live in a time where each of us will be asked to reach deeper, speak more bravely, live more from the fierce perspective of the poetic imagination; find the lines already written inside us: poetry does not take surface political sides, it is always the conversation neither side is having, it is the breath in the voice about to discover itself only as it begins to speak, and it is that voice firmly anchored in a real and touchable body, standing on the ground of our real, inhabited world, speaking from a source that lives and strives at the threshold between opposing sides we call a society.” (2016-2017)

In one of his poems he then says how, “in the silence that follows a great line..” of poetry, Lazarus can be experienced, deep down, stirring, as he “lifts up his hands to walk towards the light.” (from “The Lightest Touch”) A Church of Lazarus can be understood in just this way, as wishing to find the firm ground in the divide between life’s polarities, firm enough to embrace both, inspired by and ultimately prepared by, made possible by Christ’s moving through the macrocosmic Saturday of Holy Week.

“Between the Light and the Dark.”

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

One of the key pictures of the Passiontide Gospel Readings is that of Luke 11 and the few short verses there, referring to the candlelight under the bushel, the relationship between the light and the dark, without and within the human soul. It is often said, the brighter the light, the stronger the shadow which it casts, and again this applies similarly to external as to inner, soul conditions.

How many highly gifted people – be it artists, scientists, inspirational personalities – seem to carry within themselves a shadow side as well, where they suffer under

How many highly gifted people – be it artists, scientists, inspirational personalities – seem to carry within themselves a shadow side as well, where they suffer under

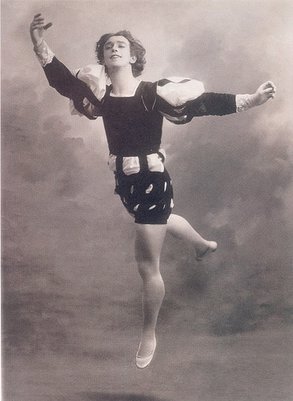

their relationship to their surroundings, also to themselves. At the moment in Johannesburg a theatre production is running on the life of Vaslav Nijinsky, the Polish-Ukranian dancer. It is based on extracts from his diaries and follows his developing breakdown as he wrestles with his exceptional talent and uniqueness, that were there from an early age. Little by little the shadow in his soul grows and is diagnosed with the limited understanding of the early 20th Century. By the age of 27 his career came to a tragic end, torn between the light and dark of his soul-life. Did his brilliance ‘get the better of him’, rather than remaining as a light placed firmly on a stool, firmly grounded to shine out and illumine the world of contemporary dance? Was he, as in other examples, ahead of his time, adding to the darkness and sense of isolation that grew within him?

It is as if Christ tackled this polemic head-on during his three years on earth, from the Temptation onward – could one say that just this was the Passion of Christ, which reaches its climax in his final months? Fielding the attacks from both sides, and trying to unite spirit-radiance with incarnation in earth-matter, the light of the world. How well He must have known, with every fibre of his being, the immensity of the task, but equally the import of that task. And how little time there was…left. Yet, as an example to us all, He was able to look from a higher vantage point and in his final hours (still) say to his Disciples:

“I stand at peace with the world.”

His mission was almost accomplished; the fusion of light and dark, a balancing act for the human soul, for which He is the forerunner.

It is as if Christ tackled this polemic head-on during his three years on earth, from the Temptation onward – could one say that just this was the Passion of Christ, which reaches its climax in his final months? Fielding the attacks from both sides, and trying to unite spirit-radiance with incarnation in earth-matter, the light of the world. How well He must have known, with every fibre of his being, the immensity of the task, but equally the import of that task. And how little time there was…left. Yet, as an example to us all, He was able to look from a higher vantage point and in his final hours (still) say to his Disciples:

“I stand at peace with the world.”

His mission was almost accomplished; the fusion of light and dark, a balancing act for the human soul, for which He is the forerunner.

“Lectio Divina”

by Rev. Malcolm Allsop

“Sacred Reading” is the most usual translation for this ancient tradition and practice of the early monks and desert fathers. Through a few ‘simple’ steps they would enter into the essence of particular sacred text, thus igniting in themselves a union with God. So the first step would be to take a piece of scripture, a piece of the liturgy, as the ‘lectio’, which is then read aloud, or, as some accounts would say, ‘bitten off’ as food for the soul. Then follows the ruminating on the content, more usually described as the meditation, that the content is gradually taken up by the heart. Out of this process comes the third stage, that of the communication with God:- “Spontaneous acts of adoration and supplication leap like sparks from the iron of the heart as the Word of God strikes upon it.” The same author then adds:- “The whole process is a strenuous one, an activity involving eyes, ears, mouth and mind.” Gregory Collins – the above source – is a Benedictine monk at the Glenstal Monastery in Co. Limerick, S. Ireland. What is interesting is that he writes on the theme in a book dedicated to the monastery’s collection of sacred Icons. As he says, in the traditional language of orthodoxy icons are in fact written, not painted, which means that they can be read and be taken as the starting point, the content of one’s Lectio Divina. Even the orthodox church buildings themselves are often seen as being icons, holy writings reflecting the workings of the cosmos. They too, therefore, are legitimate subject matter for this spiritual path.

In the well-known book “Staying Connected”, where Christopher Bamford introduces some of Rudolf Steiner’s writings on how to accompany those who have died, he also refers to Lectio Divina as a possibility in this context too: how we can reach from soul to soul across the divide.

It comes as little surprise that there is a real resurgence in interest for and practice of this path. On the one hand it offers a much missed access to the inner content of objects which are profoundly spiritual. On the other hand the range of such objects is much wider than one at first imagines. Content from Holy Texts of the world, from the Liturgy – lines from the Act of Consecration or our Epistles – are obvious choices. An Icon, (see the one in the guest room which was recently donated), opens up the extensive field of religious paintings, inspired poetry. Nature offers endless opportunity for such an exercise – the magnificence of a ripening berry, the poise of a cat, – all things which can pass us by too quickly. Each time a dialogue is initiated, by us, with an aspect of the spiritual world: be it for the deeper meaning of a particular text, a painting, be it for the God-given wonders of the world around us, be it a communing with souls who are distant or who have died, we are talking about prayer. As old as the hills but, in its many and varied forms it is being continually rediscovered and valued.

One final example: the best-selling book of Eckhart Tolle on “The Power of Now” is talking of something very closely related that has similarly been known and practiced for centuries. But he has made the discovery anew, and managed through writing of his ‘discovery’ to inspire countless others to explore this process of entering into the essence of something, in this case that of the moment, the Now. The outcome of Sacred Reading in its many guises.

“Sacred Reading” is the most usual translation for this ancient tradition and practice of the early monks and desert fathers. Through a few ‘simple’ steps they would enter into the essence of particular sacred text, thus igniting in themselves a union with God. So the first step would be to take a piece of scripture, a piece of the liturgy, as the ‘lectio’, which is then read aloud, or, as some accounts would say, ‘bitten off’ as food for the soul. Then follows the ruminating on the content, more usually described as the meditation, that the content is gradually taken up by the heart. Out of this process comes the third stage, that of the communication with God:- “Spontaneous acts of adoration and supplication leap like sparks from the iron of the heart as the Word of God strikes upon it.” The same author then adds:- “The whole process is a strenuous one, an activity involving eyes, ears, mouth and mind.” Gregory Collins – the above source – is a Benedictine monk at the Glenstal Monastery in Co. Limerick, S. Ireland. What is interesting is that he writes on the theme in a book dedicated to the monastery’s collection of sacred Icons. As he says, in the traditional language of orthodoxy icons are in fact written, not painted, which means that they can be read and be taken as the starting point, the content of one’s Lectio Divina. Even the orthodox church buildings themselves are often seen as being icons, holy writings reflecting the workings of the cosmos. They too, therefore, are legitimate subject matter for this spiritual path.

In the well-known book “Staying Connected”, where Christopher Bamford introduces some of Rudolf Steiner’s writings on how to accompany those who have died, he also refers to Lectio Divina as a possibility in this context too: how we can reach from soul to soul across the divide.

It comes as little surprise that there is a real resurgence in interest for and practice of this path. On the one hand it offers a much missed access to the inner content of objects which are profoundly spiritual. On the other hand the range of such objects is much wider than one at first imagines. Content from Holy Texts of the world, from the Liturgy – lines from the Act of Consecration or our Epistles – are obvious choices. An Icon, (see the one in the guest room which was recently donated), opens up the extensive field of religious paintings, inspired poetry. Nature offers endless opportunity for such an exercise – the magnificence of a ripening berry, the poise of a cat, – all things which can pass us by too quickly. Each time a dialogue is initiated, by us, with an aspect of the spiritual world: be it for the deeper meaning of a particular text, a painting, be it for the God-given wonders of the world around us, be it a communing with souls who are distant or who have died, we are talking about prayer. As old as the hills but, in its many and varied forms it is being continually rediscovered and valued.

One final example: the best-selling book of Eckhart Tolle on “The Power of Now” is talking of something very closely related that has similarly been known and practiced for centuries. But he has made the discovery anew, and managed through writing of his ‘discovery’ to inspire countless others to explore this process of entering into the essence of something, in this case that of the moment, the Now. The outcome of Sacred Reading in its many guises.

Hope for the Future

From The Monthly Letters of the congregation in Edinburgh, published by A. Bittleston and T. Bay.

Particularly when we begin a new year, we need to have firm hopes for the future. We need a hope both for the destiny of humanity in general, and in our own personal lives. It is difficult to achieve this at the present time, not simply because the world is troubled— there have been troubles and violent change at almost every period of man’s history—but because our physical senses make such a powerful impression upon us. More than ever before, man is inclined to imagine a future which is simply a continuation of what he sees happen externally at the moment. Cars are increasing in number: we cannot help imagining a future in which earth and air are completely infested with speeding vehicles. But man’s development does not really go in straight lines like this; the direction of his interest changes, and from every aberration he is drawn back to the things which are essential for him.

The real future is to be felt above us in the spiritual world. Emil Bock once made a remarkable comparison, in connection with the life of St. Paul. Just as it is possible to find beneath the surface of the earth, layer upon layer, the relics of the past, so, he said, the future is prepared above us, layer upon layer, among the spirits of the Hierarchies. From these realms human souls descend, when they are to enter a physical body and to live on earth. To be born, for the human soul, is a journey from the future into the present. Young children generally carry with them great reserves of hopefulness, their life in the spirit being still so near to them. And there are even some who have not come down completely into the earthly present—who have been born prematurely, for example, as was Paul himself.

Paul speaks of his premature birth in immediate connection with the appearance of the Risen Christ before Damascus. “Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.”

Paul was a man of the future; in many respects, a man of our present time. His way of experiencing the Christ was more characteristic of our present and immediate future than of his own day. Paul’s consciousness penetrated through the surface of the sense world into the realms of life, where the pure archetypes of all living things press on towards realisation in the visible. The Damascus event is celebrated according to tradition on 25th January, when nature is still without much visible change, but the invisible powers are very near to manifestation.

Man’s heart can be preserved as a vessel of hope, if the soul is active in the ways which the Magi expressed in their significant gifts, and which Paul cultivated faithfully as servant of the Christ. In prayer, the soul rises like the smoke of incense from the level of the present into the realms of promise. In the gold of the spirit, there shine the enduring Divine purposes for humanity and for individual men. And from every true, quiet attempt at meditation we carry away impulses towards positive action—impulses represented in the gift of healing myrrh. Then our freedom will help to bring the future into fulfilment.

Particularly when we begin a new year, we need to have firm hopes for the future. We need a hope both for the destiny of humanity in general, and in our own personal lives. It is difficult to achieve this at the present time, not simply because the world is troubled— there have been troubles and violent change at almost every period of man’s history—but because our physical senses make such a powerful impression upon us. More than ever before, man is inclined to imagine a future which is simply a continuation of what he sees happen externally at the moment. Cars are increasing in number: we cannot help imagining a future in which earth and air are completely infested with speeding vehicles. But man’s development does not really go in straight lines like this; the direction of his interest changes, and from every aberration he is drawn back to the things which are essential for him.

The real future is to be felt above us in the spiritual world. Emil Bock once made a remarkable comparison, in connection with the life of St. Paul. Just as it is possible to find beneath the surface of the earth, layer upon layer, the relics of the past, so, he said, the future is prepared above us, layer upon layer, among the spirits of the Hierarchies. From these realms human souls descend, when they are to enter a physical body and to live on earth. To be born, for the human soul, is a journey from the future into the present. Young children generally carry with them great reserves of hopefulness, their life in the spirit being still so near to them. And there are even some who have not come down completely into the earthly present—who have been born prematurely, for example, as was Paul himself.

Paul speaks of his premature birth in immediate connection with the appearance of the Risen Christ before Damascus. “Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.”

Paul was a man of the future; in many respects, a man of our present time. His way of experiencing the Christ was more characteristic of our present and immediate future than of his own day. Paul’s consciousness penetrated through the surface of the sense world into the realms of life, where the pure archetypes of all living things press on towards realisation in the visible. The Damascus event is celebrated according to tradition on 25th January, when nature is still without much visible change, but the invisible powers are very near to manifestation.

Man’s heart can be preserved as a vessel of hope, if the soul is active in the ways which the Magi expressed in their significant gifts, and which Paul cultivated faithfully as servant of the Christ. In prayer, the soul rises like the smoke of incense from the level of the present into the realms of promise. In the gold of the spirit, there shine the enduring Divine purposes for humanity and for individual men. And from every true, quiet attempt at meditation we carry away impulses towards positive action—impulses represented in the gift of healing myrrh. Then our freedom will help to bring the future into fulfilment.