JuneList of articles

0 Comments

Most people know that the sea contains magnesium in the form of salts, particularly magnesium sulphate. Sea salt consists on average of sixteen per cent of magnesium salts. … There is enough common salt dissolved in the earth’s oceans to build all the continents and mountain ranges. The proportion of magnesium in the salt would suffice for the building of one entire continent. By contrast with such a huge mass of magnesium, the amount of magnesium-bearing rock found in the earth’s mountains, in the form of magnesite, dolomite, and the magnesium silicates like mica, hornblende and asbestos, is negligible. …

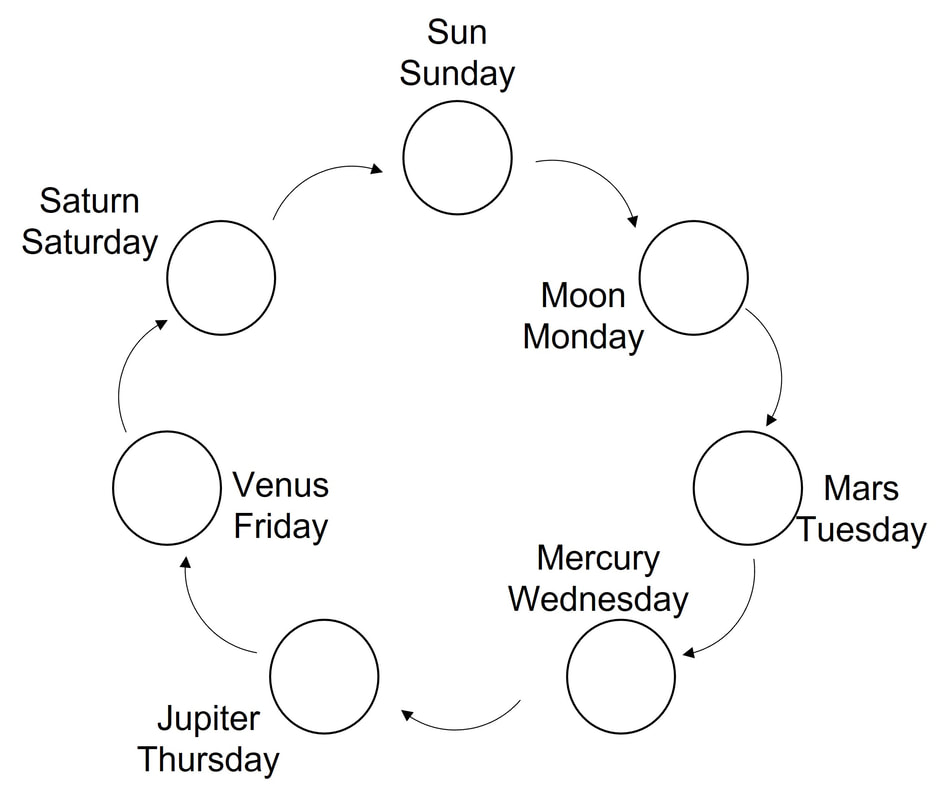

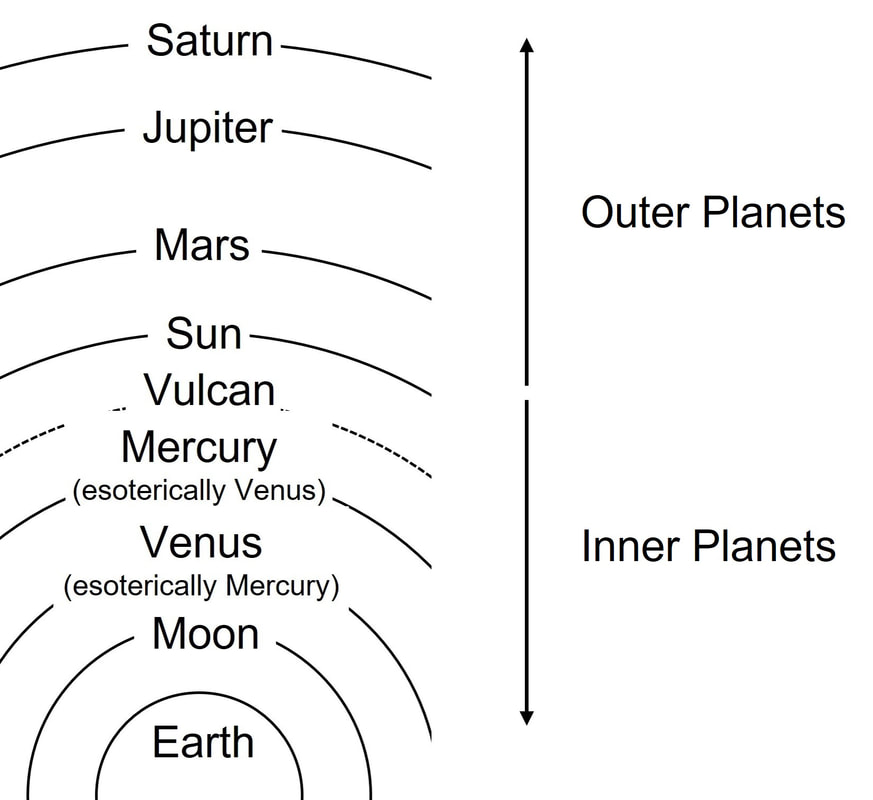

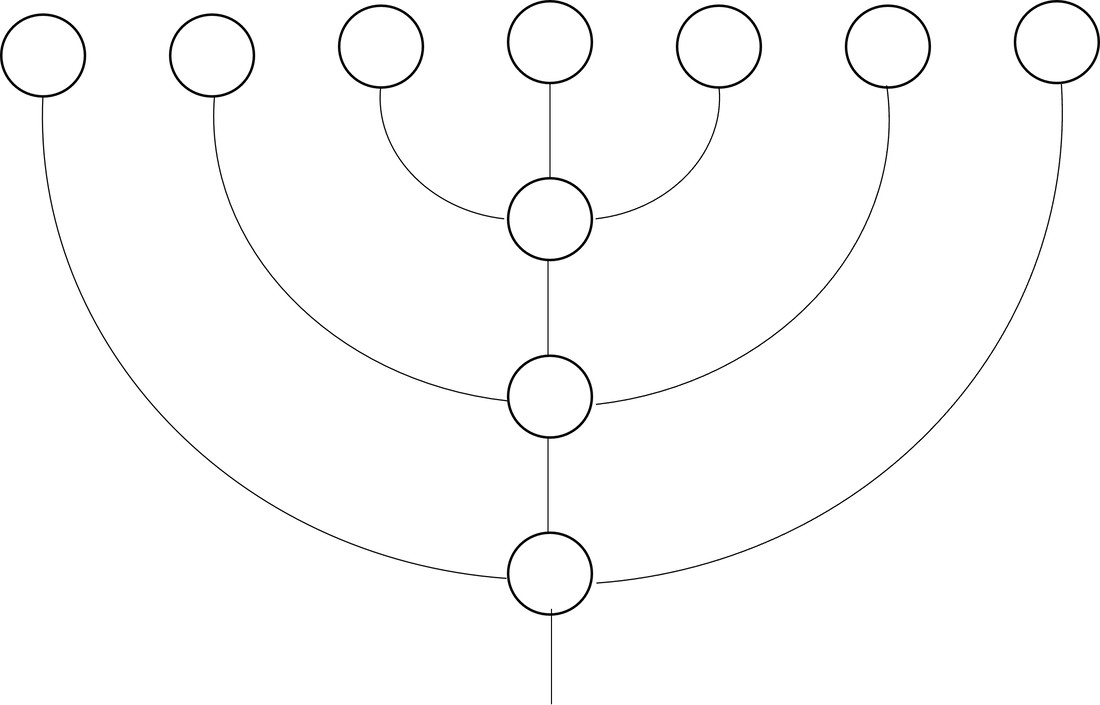

To form a conception of the nature of magnesium we shall have to concern ourselves with magnesia-bearing rock. Magnesite - magnesium carbonate - stands out, for it is used industrially in burnt form. During the firing process it changes into magnesium oxide. It is this oxide’s resistance to heat that makes it so valuable in manufacturing. High temperatures fuse an initially light, fluffy powder into rock almost impossible to melt. This capacity to resist heat, which holds up under temperatures as high as 2,000°C and more, makes magnesia valuable as a lining material in steel-smelting furnaces. So we may say that it preserves its static character even when attacked by fire, but with a behaviour different from that of lime. While lime becomes violent on firing, magnesia remains calm and gentle; it is not given to hissings, greedy devourings, and corrosive action. Quicklime is a corrosive base, which earns it the name corrosive lime. Magnesia is a mild base. Magnesia’s resistance to heat is coupled with another quality: it radiates light with an intensity hard to equal. When magnesium burns and turns into magnesia it makes a blinding white light that casts shadows even in full sunlight. So we see that the sun’s rays themselves, as they reach the earth, cannot match the intensity of light magnesium gives off. This property causes magnesium to be widely used in the making of all sorts of lighting equipment. This power to ray out, so characteristic of magnesia, also appears morphologically in the ray-formation of magnesium-bearing rock. Magnesium silicates, such as actinolite, serpentine, talc, asbestos, and the like, tend especially to a radiating or fibrous structure, reminiscent - as asbestos is - of textile fibre. Asbestos (was) actually used to make fireproof thread, cloth, rope and wall-boards. A further phenomenon is produced by magnesium’s affinity to light. Those who have visited the southern Tyrol and witnessed there the glorious spectacle of the ‘Alpine glow’, will remember its beauty for the rest of their lives. These mountains, the Dolomites, are built of so-called dolomitic limestone, an isomorphic mixture of calcium carbonate and magnesite. It is harder than ordinary limestone and does not as a rule have the radiating structure usually found in magnesia rock. But when the sun has sunk behind the horizon, the light these peaks have absorbed shines out at the onset of darkness with a gentle rose-red glow. This unparalleled affinity to light possessed by magnesium explains its presence in the substance chlorophyll and the role it plays in assimilation. Plants, as we know, are made of light, and in the sheaved rays of cellulose fibres we really have, so to speak, materialised sun rays. Here magnesium shows itself in the role of a light-propellant in assimilation. It is magnesium that thrusts light into the dense materiality of starch and cellulose. The same propulsive forces are at work in spring when seeds, which contain considerable amounts of magnesium, begin to germinate, often thrusting up heavy layers of earth or snow in the process. The same dynamic function serves the human organism wherever solid matter is excreted or separated off from fluids. We see this happening most obviously in the digestive process, at the point where waste matter is separated out of the chyme and takes on a firmer consistency. The drastic effect of ingesting Epsom salt (magnesium sulphate) indicates the close connection of magnesium with intestinal functioning. Deep inside the organism there are other eliminative processes which must be recognised as such. One of these is the depositing of bone-building matter in the skeleton, likewise a moulding of solids out of fluids. This process is most obvious in young children, whose organisms are still very plastic and as yet scarcely mineralised. Their bones are subject to a hardening process that reaches its culmination and completion in the emergence of the second teeth, the last and hardest product of the body. At this point the solid organism has been separated from the fluid. And forces that previously served organic functions are now set free, in the form of a capacity to think and remember, making the child ready to begin his schooling. It is the magnesium process which we see at work in all such developments. On the one hand it plays the role of a hardening agent, compressing life into solid earthly form. On the other it activates light-forces. Thus it combines startlingly contrasting functions. These contrasts are represented in zodiacal imagery as the centaur. His horse’s body symbolises ties with earthly animality, yet with the rest of his being he raises himself to a luminous human height. In mythology the picture of the centaur with his bow and arrow has always been the symbol of these contrasting forces. The ancients experienced them as proceeding from that part of the heavens known as the constellation of the hunter, Sagittarius. report by John-Peter Gernaat This workshop by Rev. Michaël Merle opens up three periods of our biography: the early childhood period before seven years of age, the childhood years of seven to fourteen and the years of youth, fourteen to twenty one. How can we delve into our toddler years when we have very little memory of those years? We may have been told by parents that we had a challenge to overcome? Or we may recall ourselves that there was a life challenge that we had to overcome. We can find a way of integrating this life challenge through fairy tales. Fairy tales have archetypal characters. A king is a king, a witch is a witch. There is no need to personify these characters. The secret in fairy tales lies in that all the characters that show up in a fairy tale are a part of the listener. There is no one in a fairy tale who is outside the listener. We all have the wicked witch in us, and it is okay for her to die. We all have a prince charming in us who rescues the day. Michaël introduced us to Jung’s archetypes. He placed the twelve archetypes into quadrants. Each quadrant speaks to an archetypal desire: a yearning for paradise, leaving a mark on the world, connecting with others, and giving structure to the world. We may feel drawn more strongly to one of these desires. Within each quadrant there is an archetype that speaks to what Jung understood to be our ego nature, our self-nature and our soul-nature. Identifying one archetype provides the central character of the fairy tale. Our challenge was to write a fairy tale in which the central character (identified from the archetype within the quadrant of our dominant yearning) overcomes a challenge, in typical fairy tale style. Every character that appears in the fairy tale is an aspect of ourselves. These characters may appear of their own accord during the writing, and it becomes a valuable exercise to identify each character within ourselves and how they have helped us overcome the challenge. Significant role players in our early childhood could also appear but only as a projection of our relationship to them. For some members on the workshop this exercise revealed aspects that they had as yet not been able to integrate into their lives. The fairy tale does not reveal any personal secrets except to the writer. Anyone else hearing the fairy tale may relate to it in a very different way, recognising other aspects of themselves rather than the hidden secrets of the writer. The period age of seven to fourteen presents a very different stage of life. Rudolf Steiner gave a lecture on how we would ideally experience the four temperaments, one in each seven-year cycle of development culminating in an adult who can draw on the temperament most suited to a situation but generally operating as a healthy choleric, being able to say “yes” and “no” to the things that present in life in a healthy way. However, our development is seldom ideal and we live with the consequences of drawing in a latent or premature temperament into childhood. Each temperament is associated with an element. We created a totem pole for ourselves onto which we identified our totem animal in each of the elements that resound with the temperaments: from earth, water, air to fire, being melancholic, phlegmatic, sanguine and choleric. Selecting the totem animal we most identified within our childhood years, we wrote a fable. A fable is a story in which the characters are all animals. These animals are anthropomorphised, rather than behaving as animals would in nature. However, a central characteristic of the animal forms the basis of the tale, e.g., a hare that runs fast and stops, while a tortoise is slow but steady. The central character is the one with which we identify while the other characters appear in the fable to teach the central animal a lesson. The fable we wrote was about our central animal learning something of value from an animal of very opposite character. Then we wrote a fable in which our main character had to overcome a challenge entirely alone. Other animals that might appear were subsidiary to the main character overcoming the challenge and not there to assist. It was interesting coming to terms with something I saw as a challenge in childhood through writing about it in a way that brought resolution. The years of youth are guided by the planetary soul types. It is quite easy to recognise the planetary soul type of a young person. Set a task and see how they behave. In this workshop Michaël created an imaginary situation and we had to identify how our young self would have behaved. There were six behaviour options and therefore it was quite simple to make a choice. The choice seemed obvious, until we added the planet to each behaviour type. The first reaction might have been to reject that as our planetary soul type, but a little bit of thought very quickly clarified that this was indeed our “home planet”. Michaël shared the rhythm of the planets according to the cycle of the week, which when we look at the relationship of each planet to the sun from our earth perspective reveals a rhythm from inner to outer planet and back: This means that the correct order of the planets is:

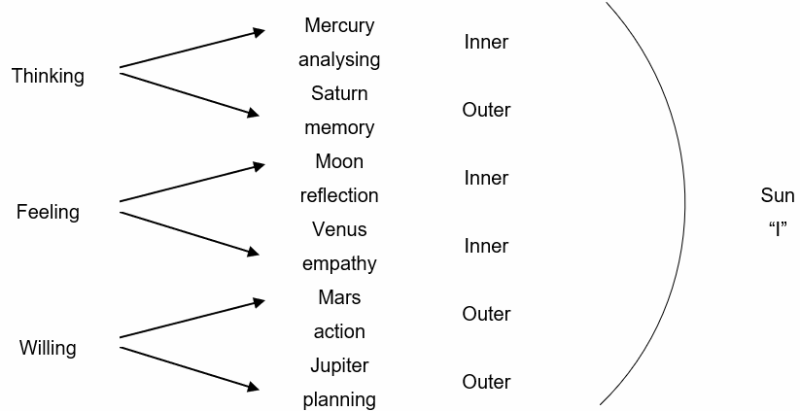

This is the proof that the names of Venus and Mercury were switched around at some point after the naming of the days of the week. What are the soul capacities of each of the planetary soul types: The planetary soul types become illumined by the light of the sun when the Ego is “born” at adulthood. Although we will always retain our “home planet” the sun (“I”) enables us to move freely to any other planetary soul type for which a situation calls. Once we had each established our planetary soul type, we wrote a letter to our teenage self from the perspective of our adult self (the self now illumined by the sun) reassuring our younger self that life would be amazing. Thereafter the letters were ‘mailed’ to our teenage selves, and we were able to read them aloud privately as our teenage selves receiving the reassurance of our future adult selves. This process was quite revealing. We forget something that Michaël pointed out: teenagers are able to feel, but not able to think. Teenagers have a great desire to express what they are feeling. The mistake is to think that what a teenager expresses comes from thinking. I recall so much ‘thinking’ that I did as a teenager and the impressions of all that ‘thinking’ (silently expressing to myself) still live quite acutely with me. This exercise was able to shine the light of the sun (the “I”-constitution) very clearly onto that part of my life and put into a correct context. It lifted a great weight from my shoulders, not because I resolved anything through reflective therapy, but simply by being able, at last, to place it all in a context that, within my life’s biography, makes sense. These three workshops are difficult to characterise. Each workshop dealing with a different period of life and different style of writing, together forming a step-by-step process that takes the puzzle pieces of life and slots them into the correct places to produce a clear picture. This is unlike other biography workshops that rely on a reflection back across one’s life to find all the puzzle pieces and analyse them, hoping in the process of analysis that they will reveal their correct place in the picture. This series of Biography Through Story workshops is gentle and the results can be pondered for a long time, because they are revealing rather than disturbing or traumatic. Reviews from other participants:“To clearly understand, express and integrate who we are as individuals has never been more needed than now. The Biography Through Story series of workshops facilitated by Michaël Merle were for me truly wonderful. I deeply appreciated how the process and stories were clearly explained and unpacked for us each to use to personally explore our own biography. While the freedom of expression was encouraged, the privacy of each participant’s work was absolutely respected. This I believe was the key as to why each session worked so well. Thank you Michaël for this very refreshing and rewarding experience.” - Adam Botha The Biography Through Story workshop by Rev. Michaël Merle gives us as participants a wonderful opportunity to delve deeper into the archetypal characters of man and animal and the planets. By doing that we are empowered to look into our own biographies from early childhood to adulthood with imagination and empathy. Thus, we discover new ways of understanding ourselves and our lives. The positive aspect of the method Michaël uses gives us confidence and trust to plunge into our past with enthusiasm in order to write our own fairy tale and fable. In the discussion following the writing session we are free to share our feelings and experiences if we wish. I have participated in various biography workshops in my life but none as innovative, creative and relaxed as this one.

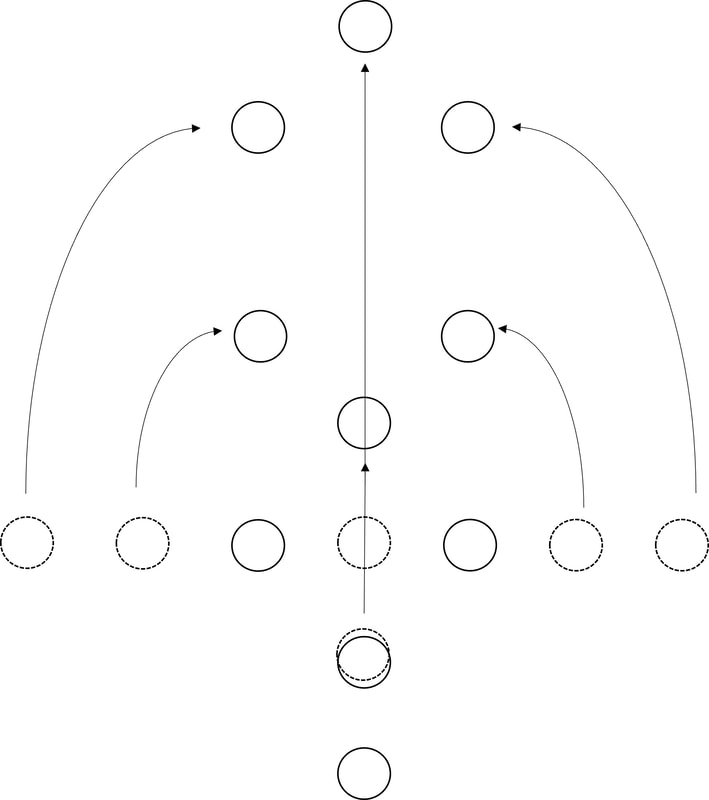

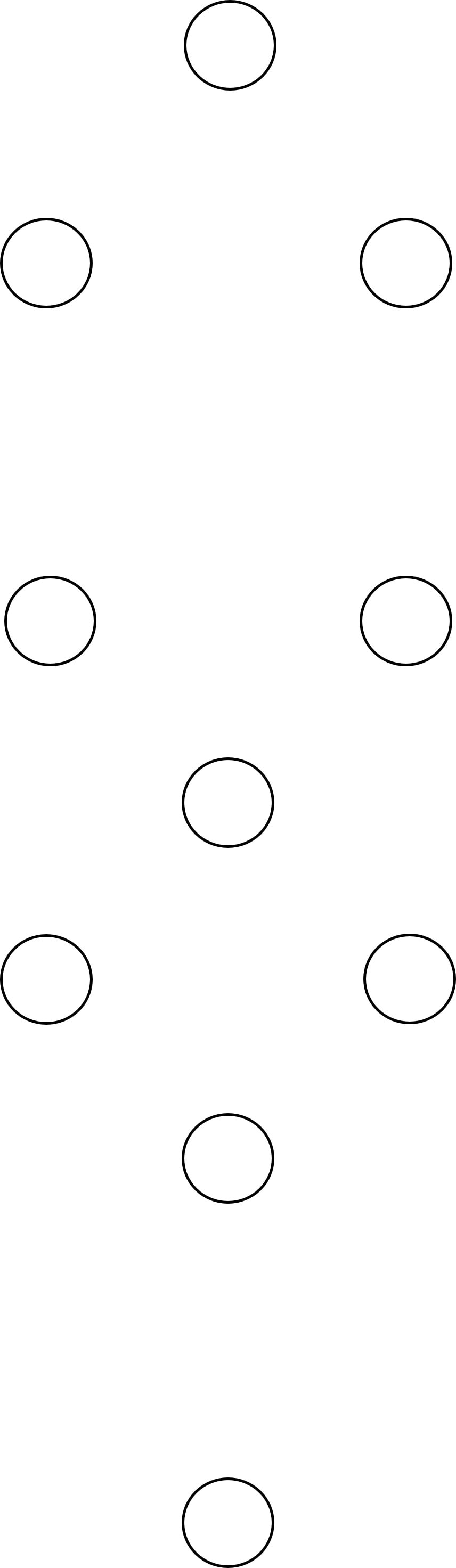

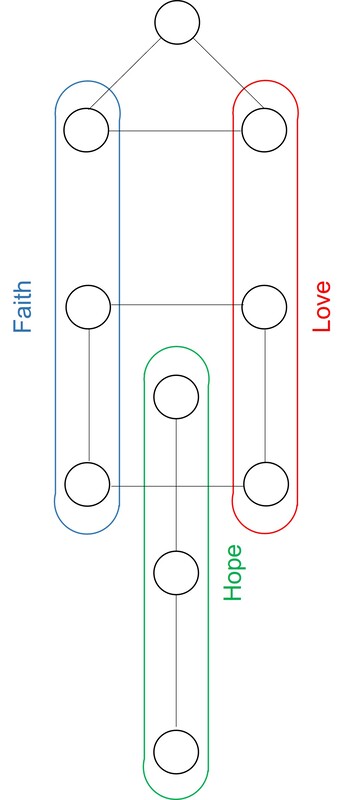

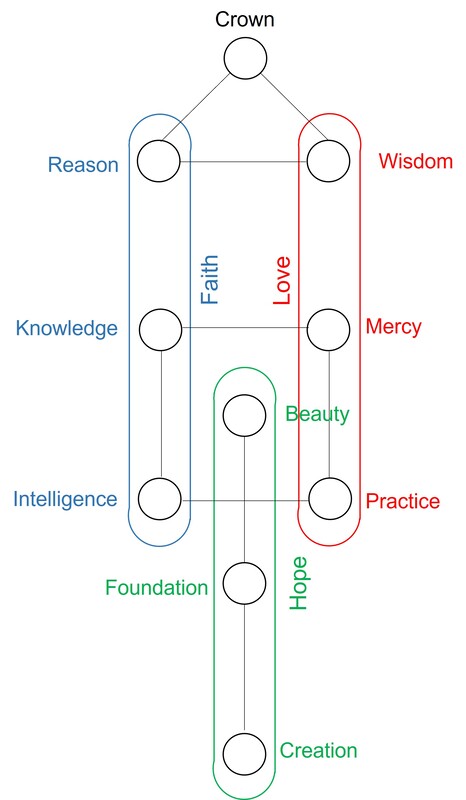

Wiebke Holtz report by John-Peter Gernaat In the Garden of Eden there were two Trees described as being in the middle. The one Tree was the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. ‘Good and Evil’ is a merism and means ‘all things’; It could therefore be described as the Tree of the Knowledge of All Things. The other Tree was the Tree of Life. Both of these are esoteric trees, not physical trees. Deeper study reveals that they for part of a set of seven Esoteric Trees that coincide with the development of the human being through the Great Cycles of Time. The Tree of the Knowledge of All things is the Tree of this Earth Cycle of Time. This means that the intention of this Earth Cycle of Time is for the human being to become the Tree of the Knowledge of All Things. It was therefore not the intention that humanity should not eat of this Tree, but humanity chose to eat of the fruit of this Tree before the human being had the constitution to discern all of this knowledge. Eating of the fruit of this Tree therefore had an effect on the development of humanity that was not in the original intention. The incorporation of the I-constitution into the human being through the event of Whitsun brought the human being to the developmental point of being able to discern the Knowledge of All Things. The Tree of Life is the Esoteric Tree for the next Great Cycle of Time. We receive a picture of this Tree in Revelation where it is described as being on this side of the River of the Water of Life and on as being on that side of the River in the New Jerusalem. This picture is of two avenues of the Tree of Life standing along the River of Life. The Tree of Life in the New Jerusalem is described as bearing twelve-fold fruit, a different fruit in each month, and having leaves that heal the nations. It is a picture of the becoming human being in the next Cycle of Time: the human being becomes the Tree of Life. Human beings appear, by all scientific investigation, to have their origin in the region between the Cradle of Humankind and the Ngorongoro Basin and to have left Africa to populate the middle east, migrating along the seashores to the far east and having travelled to Australia between 70 000 and 80 000 years ago. A second migration is more recent. From these migration cultures eventually arose and these cultures have left records, the earliest being, broadly, from around 10 000 years ago. The first great culture recognised the Tree of Life as a real tree, a mighty banyan tree that grew on the banks of the Ganges River. The second great culture identified the Tree of Life as being rooted In the Water of Life and guarded by two Ka fish that swam around the roots of the Tree in opposite directions (the earliest picture of the constellation of Pisces) protecting the Tree from a poisonous toad. This was the Sumerian Culture. The third great culture identified with a Tree of Life and Death which was an acacia tree for the Egyptians. The first people walked out of the Tree of Life and Death. Life was the beginning for the Egyptians but the greatest part of the journey occurred in death. In the fourth great cultural period the Tree became the Tree of Death and Life represented by the Cross; resurrection arises out of death. After the 15th century AD the development of the human being gave rise to the consciousness soul. The Kabbalah Tree of Life is a picture of the Tree of Life that has arisen from the Consciousness Soul Age. It is relevant because it is not a fixed picture. There is a lot that can be understood from the Kabbalah Tree of Life. However, be cautioned that very little of the writings of those who have investigated the Kabbalah Tree of Life most profoundly, both Rabbinical and Christian scholars, is accessible through a search of the internet. The information that is readily available on the internet is misleading and biased. The great gift of the Kabbalah Tree of Life is that it can be understood in many ways. Kabbalah means ‘real’ or ‘to receive’. The Kabbalah Tree of Life is represented as ten sefirots which means attributes or characteristics of the Divine. We may see the Kabbalah Tree of Life as having been received from an earlier image. The points move upwards as indicated below:

The first leader of the priest’s circle in the history of The Christian Community was Friedrich Rittelmeyer. Understanding how he came into the Movement for Religious Renewal from Alfred Heidenreich’s view may prove of interest to us as a way to look back on our history in order to look forward to our future. Rittelmeyer was a prominent Lutheran pastor in Germany in the early part of the 20th Century.

Early in 1917 Rittelmeyer was called to Berlin, to one of the most influential pulpits in Germany, comparable perhaps to the pulpit of St. Paul’s or the City Temple in London. Of his experience in this position during the last two years of the First World War, when he saw the final collapse of Imperial Germany at very close quarters, he spoke with many vivid details in his autobiography. By the end of the war he had gained an international reputation. Archbishop Soederblom of Sweden invited him to visit the Scandinavian churches. As a member of the German section of the Ecumenical Council Rittelmeyer was chosen to meet the group of leading Quakers who were the first Christian representatives of Britain to extend a handshake of peace to the Germans, and to welcome the first delegation of American bishops. It seemed then only a matter of time until Rittelmeyer would be offered the highest position in the hierarchy of the Lutheran Church in Germany. However, events took a different turn. Rittelmeyer was in his forty-ninth year, when the turning point of his life came. Providence offered a helping hand, but did not force the issue. In 1918 he had met with an accident, in which he broke a leg, but which was not otherwise considered serious at the time. Delayed after-effects of some internal injuries compelled him, however, to go on sick-leave in the summer of 1920, and to retire from public life for nearly a year. On his sick bed he prepared the greatest public tribute to Steiner that had yet appeared. He prevailed upon a number of leading men in various walks of life who by that time had been earnest students of Rudolf Steiner’s work, to say in the form of a comprehensive article what they owed to him in the field in which they were masters. Rittelmeyer edited these collected essays and himself contributed one called ‘Rudolf Steiner’s Personality and Work’ and one called ‘Rudolf Steiner and the German Spirit’, the latter a deliberate challenge to the resurgence of militant nationalism. The work appeared as a birthday gift for Rudolf Steiner’s sixtieth birthday in 1921. It was the first substantial tribute to him published by an ‘outside’ publisher. It was a great challenge to the German intelligentsia at the time. Rittelmeyer published later in his autobiography one or two characteristic letters which he received at the time from leaders of contemporary thought, charming and pathetic in their non-comprehension. During this period of enforced physical inactivity Rittelmeyer found time to ponder in detachment over the proposed movement for religious renewal of which he had been kept informed from the beginning. What went on in his mind in those months was decisive. When he had sufficiently recovered to meet us, his mind was made up. I remember very well his first appearance in our circle in Berlin in the late autumn of 1921. I must confess that for me it was something of a shock. Of course I was deeply interested and in a very real sense already committed to this coming movement for religious renewal. But anything even faintly parsonic or reminiscent of religion in the usual style sent cold shivers down my spine. It was inevitable that at that first meeting with us Rittelmeyer should still show something of the exterior of the Lutheran parson. Later on he transformed this in the most exemplary and moving manner. But for the moment some of us had to swallow hard. It was all part of the historic process. In the following spring of 1922 during another of these conferences for university students, we had a decisive meeting with Rudolf Steiner in one of the vestries of Rittelmeyer’s church in Berlin. Steiner strongly encouraged those among us who wanted now to go ahead. Soon after, Rittelmeyer offered his resignation from his position in the Lutheran Church. As a matter of fact, his letter of resignation was not even acknowledged. The ecclesiastic authorities did not write a single line of thanks or regret to the man who had given the church a quarter of a century of historic service. In the summer of that year, Rittelmeyer, Geyer and Bock, who were expected to become the leaders of the movement, were invited by Steiner to spend some time with him in Dornach for top level conversations. In these talks, which continued for several weeks, the principles of leadership in a modern Christian community were clarified. |

Article Archives

December 2022

2023 - January to December

2021 - January to December 2020 - January to December 2019 - January to December 2018 - January to December 2017 - January to December 2016 - January to December 2015 - January to December 2014 - November & December 2013 - July to December 2013 - January to June 2012 - April to December Send us your photos of community events.

Articles (prefaced by month number)

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed