|

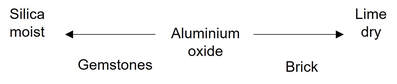

From the book The Nature of Substance: Spirit and Matter by Dr Hauschka Aluminium and Phosphorus Clay is plastic and responsive to formative forces working on it from outside. Just as a musical instrument responds to a musician so plastic clay is the instrument for the music of forms composed by a sculptor. It is the aluminium process that makes earth receptive to the cosmic shaping forces of the silica process which the great artist, Nature, draws from the cosmic periphery. Silica’s affinity to water appears again here in relationship to clay, for it is only when clay is properly moist that it is sufficiently plastic to be receptive to the shaping activity of silica. But the formed clay becomes static in the drying process, while firing makes it almost indistinguishable from lime. Pieces of sculpture, pottery and bricks are all rendered hard, dry and porous in the kiln (pottery is given a skin of silica in the process called glazing). The lime in mortar holds together the bricks in the house-walls which shelter and support our physical life. Again we see aluminium-bearing clay as the balancing agent between silica and lime. Of course, there are latent polarities in clay. In itself it is the least aristocratic substance; the forms built of it are the most transitory. This is expressed in the Biblical picture of man’s transitory physical body formed of clay. We might say, borrowing this picture, that man is built from head to toe out of such a balancing of heavenly and earthly forces as clay affords. But this ‘clay’ undergoes a stage by stage upward purifying as man refines it in his various organs, reaching a peak in the eye’s transparency; here dark earthly matter has been raised to a level where it becomes permeable by the light of spirit. Clay thus serves also as a gemstone matrix. Gems are the highest stage of mineral matter, perfect expressions of the harmonious interplay of lime and silica, of earthly anchoring and cosmic shaping. Almost every kind of precious stone is made of aluminium oxide or of a compound of aluminium. The family of corunds, rubies, sapphires, consists of pure aluminium oxide. Other gems, such as tourmalines, emeralds, topazes, zircons, contain aluminium compounds. In precious stones, aluminium lends itself wholly to silica’s cosmic shaping forces; in brick it is given off both to dry, static earthly force of lime. Putting a ruby, with its brilliant red, beside a soft blue sapphire brings home the fact that jewels are a synthesis of polarities at the very highest level of which matter is capable.

There is a wonderful gemstone that combines two polar colours in each single crystal. This is the tourmaline, with its complementary green and purple (sometimes pink). Turning to the human being, whose physiology lies between skin and skeleton, silica and lime, we find an element which as the carrier of physiological processes moves in ceaseless rhythm between polar opposites. This is the blood, which streams out to the periphery of the body and then returns to its innermost core. As it moves toward the skin and the extremities, blood is red; on its return journeys blue. The heart is like a jewelled expression of this active synthesis. Its beating is a rhythmic harmonising of these poles. How understandable it seems in the light of these facts to apply aluminium (in the form of aluminium acetate or clay poultices) in treating congestions inflammations, sprains and bruises. Felspar (orthoclase) externally applied, also helps to harmonise heart action. In contrast to clay, phosphorus (or phosphate rock) is thinly scattered through the earth’s crust, like spices in a cake, instead of filling up whole regions, valleys and basins. Rarely are phosphate deposits sufficiently concentrated to make mining them worth while. This mineral, found chiefly in the form of calcium phosphate or apatite is much sought after by manufacturers of superphosphate a well-known artificial fertiliser. But phosphorus is everywhere in minute quantities. Humus derives it from decaying plants and plant-ash has it in considerable amounts. Where dead plant-matter piles up in layer on layers in swamps or on moorlands, decomposition releases an organic compound in the form of phosphene: PH3.

0 Comments

|

Article Archives

December 2022

2023 - January to December

2021 - January to December 2020 - January to December 2019 - January to December 2018 - January to December 2017 - January to December 2016 - January to December 2015 - January to December 2014 - November & December 2013 - July to December 2013 - January to June 2012 - April to December Send us your photos of community events.

Articles (prefaced by month number)

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed